The Work

In her novel The Abyss, Marguerite Yourcenar quotes an alchemical saying: obscurum per obscurius; ignotum per ignotius, which roughly translates, proceed toward the obscure and unknown through the still more obscure and unknown.

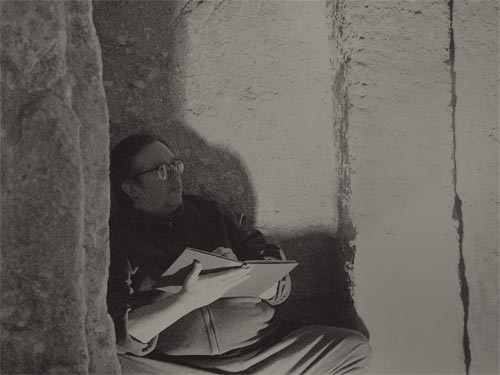

All my work begins with my dreams, recorded in sketchbooks with narratives and drawings. These dreams are often prophetic, telling me where I need to travel to work — to make one world, one cosmology, where the seen and the unseen co-exist.

Once my dreams have led me to a site, I develop my pieces slowly, carrying them back and forth between sites, cross-pollinating ideas, locations, and subject matter — all united in the studio. Time is no longer linear, but elastic, continuous, and circular.

In Italy I have worked in many closed mithraeums (the man-made caves of the astrological cult of Mithras), the Roman Colosseum’s hypogeum, Etruscan ruins, the temple at Gabii, in churches and archeological sites throughout southern Italy and Sicily (especially in Matera, Alberobello, and Otranto), and in numerous catacombs — all closed to the public. Outside of Italy, my dreams have led me to Mayan sites and abandoned silver mines in Mexico, to the top of the Parthenon in Greece, down into the ancient, abandoned quarry on the island of Paros (famous for its translucent marble), and in Central Turkey, to the cryptic frescoes within monasteries and underground cities in Kapadokya.

The catacombs — my primary focus — are silent mazes, cold and dank. Skeletons, nearly two thousand years old, embrace one another in their tombs, and, if disturbed, would turn to dust. Paintings and carvings form mysterious, iconographic hybrids of an emerging spiritual language. Worms with millipede-like legs coexist with 10-inch long phosphorescent mantises that give off an eerie green light. Blind translucent spiders the size of my hand make clicking sounds on the tunnel walls while aphids skitter by the thousands up stalactites.

In addition to my “dream-books” and paintings, I have built a library of sketchbooks that form an archive of images from museums, archeological sites, and landscapes. Using these combined tools I want my search to be a gift that visualizes the most arcane cosmology, where intimate secrets lead to endless questions and possibilities.

Sketchbooks: Salt Spiders, Triplets and Sleep

My studio is on fire, so what do I grab? No pets here; it's my sketchbooks. Carefully annotated and lined up on shelves, I would need a chute to send these stacks and stacks out the window, but they must be saved for they are my encyclopedia, my secrets.

Ever since I can remember I have kept three kinds of sketchbooks, all carefully annotated and cross-referenced.

First, in hand-made hardbound books, I draw, paint and collage everywhere: from subway tunnels to museums; beside hospital patients and at chamber concerts. Second, because I am a compulsive drawer, I keep “sketch boxes” wherein I put myriad drawings made on meeting agendas, waiting-room magazines and assorted scraps.

The third kind of sketchbooks I keep are my bound, hardcover “dream books”, one of which is always by my bedside, accompanied by writing and drawing implements. I know through experience that without my book and materials at hand that the recurring dreams and prophetic dreams on which my work relies would dissolve into the early morning ether. My ritual is this: early each morning I write down my dreams, often adding drawings and “maps” because, for as long as I can remember, places, animals, departed loved ones, disturbing events and the elastic conundrum of time form a seemingly endless inner world that occurs, for the most part, underground. It is this underground dream world, more real than what I see as I write this, that has vividly “told me” what to explore and where to work on-site.

These “real” spaces feed my dream life, alter time, and coalesce into one, unbroken cycle of waking and sleep.

Teaching

In his commentary on Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet, John Lanchester says this book “does for [modern] man what Montaigne did in the 16th Century… In a time which celebrates fame, success, stupidity, convenience and noise, here is the perfect antidote, a hymn of praise to obscurity, failure, intelligence, difficulty, and silence.”

For what is the purpose of creativity but to actively seek the deepest insights into humanity through the crucible of making, and more importantly, un-making?

Despite increasingly precise measurements, contemporary maps of the cosmos or the minutiae of the sub-atomic world will likely be no more accurate in the future than ancient seafaring maps that included half-remembered landscapes and sea monsters.

Like mapmakers, we draw and paint what we observe, but find our drawings inevitably cross over into the unknown, for, like maps, they are never truly, wholly accurate, never allowing for shifting points of view or even the necessity of dreams.

This then is our region – where the visible and invisible meet, where the observed and the intuitive lie side by side, and where the seen pays a constant debt to the unseen.

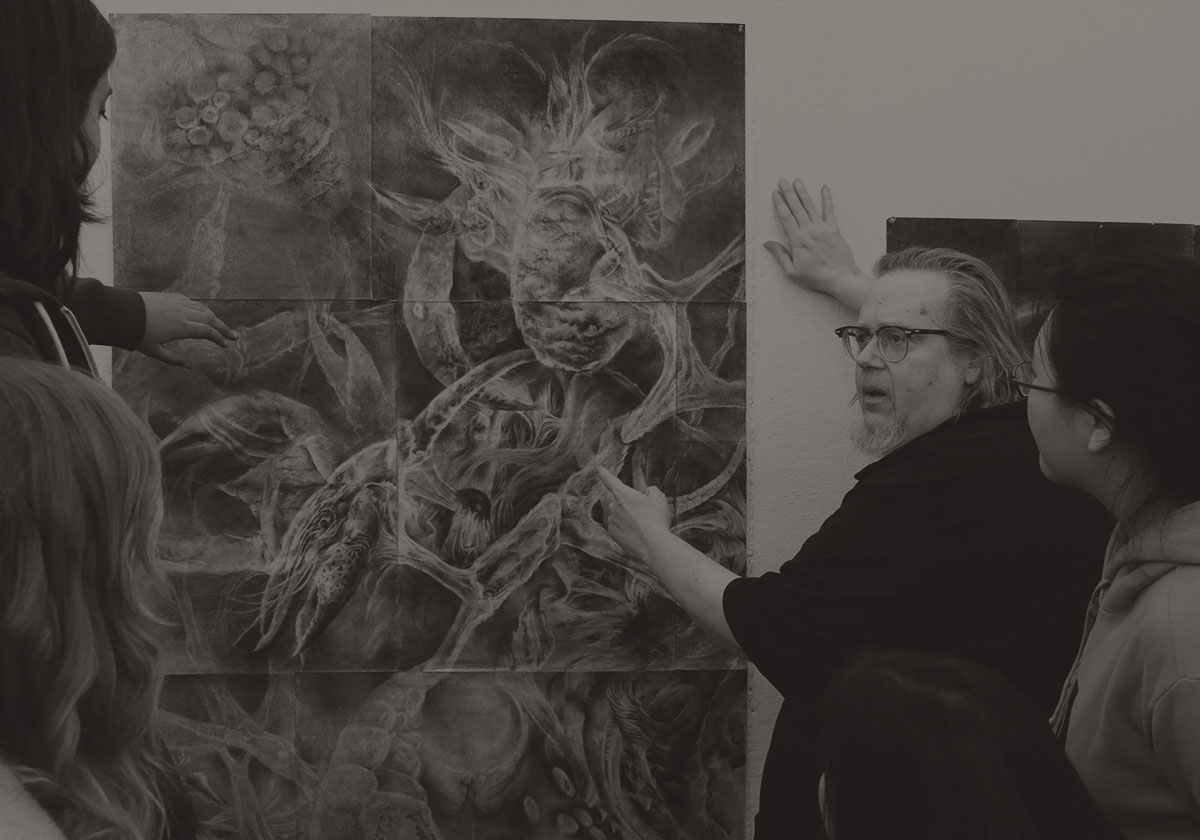

Everything changes when we draw: channels open up between our eyes and our breathing, heart rate, and neurological paths. Borders dissolve between touch, smell, and sound. The ideas absorbed when we draw are infinitely better than when we don’t draw. And, like making maps, what we draw we remember; what we don’t draw, we forget.

But like maps, drawing is about the specific, not the general: about revealing ideas with precision and authority. Ironically, it is the discrepancy between one’s unfocussed marks – one’s lack of precision compared with the purity of the subject, full of complexity and unseen forces at work – that leads to the prolonged search.

The initial marks we make are only the beginning: it is when we begin to unmake these marks through sanding and erasing, that drawing becomes thinking. By deliberate and often painstaking removal, by excavating, the drawing starts to reveal its true self. Clouds of erased marks ensue, and the search is fully underway.

Acknowledgements

Were it not for the things we make and for those we love as evidence of a life lived, what we call Time might leave life hopelessly incomprehensible. After over thirty years of living on and off in Rome, Time, on the one hand, laughs at how little I have seen. On the other hand, the friendships I have made are resilient to the whims of the calendar. Thirty years in Rome is nothing, but thirty years of friendship is more than many less fortunate will ever experience.

To Ezio Genovesi, Director of the Rhode Island School of Design’s European Honors Program, my first friend in Rome: I cannot imagine doing what I have done without his wisdom, generosity, and the closeness I feel for him, his talented wife Laura Graham, and their children. To Peter Gardner and Barbara Foley, Luisa Guarneri and Jonathan Hynd, Cinzia Abbate and Maryann Fennimore Kranis and family: they are all visionary and humane thinkers who like strong gravitational planets keep me centered.

My work in the catacombs would not be possible without the vivacious support of Valentina Luciani, and the mystical presence of Padre Alessandro Venturin, who seems to accompany me even when he is not there. I am further indebted to the support, inspiration, and kindness of Don Edoardo Parisoto and Don Franco (Francesco) Gualtieri, as well as to Silvia Orlandi, whose scholarship in the study of ancient texts is invaluable, and to Dante Braido, whose gardens are a place of tranquility and great beauty.

Over the years I have been embraced by the individuals who watch over and protect the Colosseum: together we relax after closing and celebrate holidays as a family. To Filippo Favale, Paolo and Cinzia Pescosolido, and Stefania Pagliaricci, who together know no limits to the word “generosity”. The feast that Filippo, Paolo, Cinzia, and Stefania arranged with Massimo and Cinzia Vennetilli at the mysterious site of Gabii may be the happiest day of my life.

I wish to thank Frank Maresca, who is perpetually incisive, brilliant and full of a vivacious spirit to which we all can aspire.

Above all, this site is dedicated to the love of my life, Susan Werner.

Ringraziamenti

Se non fosse per le cose che facciamo e per coloro che amiamo a testimonianza di una vita vissuta, quello che chiamiamo Tempo, con la sua natura elastica, lascerebbe le nostre vite irrimediabilmente incomprensibili e senza senso. Dopo oltre trenta anni in cui ho vissuto più o meno frequentemente a Roma, il Tempo sembra irridere rispetto a quanto poco ho visto. Trenta anni a Roma sono niente, ma Trenta anni di amicizia sono molto di più di quello che persone meno fortunate di me avranno mai la possibilità di vivere.

I miei ringraziamenti vanno dunque a Ezio Genovesi, Direttore della Rhode Island School of Design’s European Honors Program, il mio primo amico a Roma: non riesco a immaginare come avrei fatto senza la sua saggezza, la sua generosità e la vicinanza che sento per lui, per la sua valente moglie Laura Graham e per i loro figli.

A Peter Gardner e Barbara Foley, Luisa Guarneri e Jonathan Hynd, Cinzia Abbate e Maryann Fennimore Kranis e sua famiglia: pensatori visionari e umani che come forti pianeti gravitazionali mi hanno aiutato a rimanere centrato.

Il mio lavoro nelle catacombe non sarebbe stato possibile senza l’attiva assistenza di Valentina Luciani e la mistica presenza di Padre Alessandro Venturin, che sembra accompagnarmi anche quando non è presente. Sono inoltre debitore per il loro sostegno e per la loro gentilezza ai seguenti sacerdoti: Don Edoardo Parisoto e Don Franco (Francesco) Gualtieri, e anche Silvia Orlandi, la cui competenza nello studio dei testi antichi è stata insostituibile, e Dante Braido, i cui giardini sono un posto di quiete e di grande bellezza.

Nel corso degli anni sono sempre stato accolto con simpatia dai sorveglianti e dai curatori del Colosseo: insieme passiamo qualche momento di relax dopo la chiusura e celebriamo le festività come una famiglia.

A Filippo Favale, a Paolo e Cinzia Pescosolido, a Stefania Pagliaricci: nessuno di loro conosce i limiti della parola “generosità”. a festa che Filippo, Paolo, Cinzia, e Stefania hanno organizzato insieme a Massimo e Cinzia Vennetilli nel misterioso sito archeologico di Gabii la ricorderò come uno dei giorni più felici della mia vita.

Vorrei infine ringraziare Frank Maresca sempre molto acuta, brillante e piena di quello spirito vivace che tutti vorremmo.

Ma soprattutto, questo website è dedicato al grande amore della mia vita, Susan Werner.

Colophon

Photography was provided by Karen Philippi at Philippi Photographi, Erik Gould, Rhode Island School of Design, Russell Rudzinski and Susan Werner.

This website was designed and built by Micah Barrett.